Behaving sick: weighing the social costs and benefits

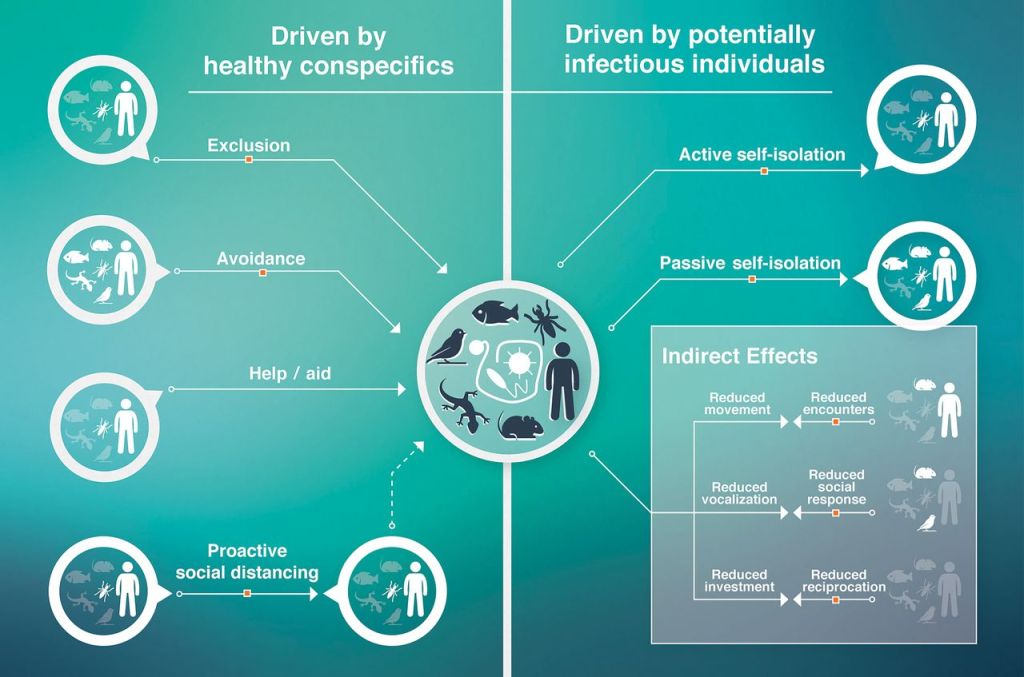

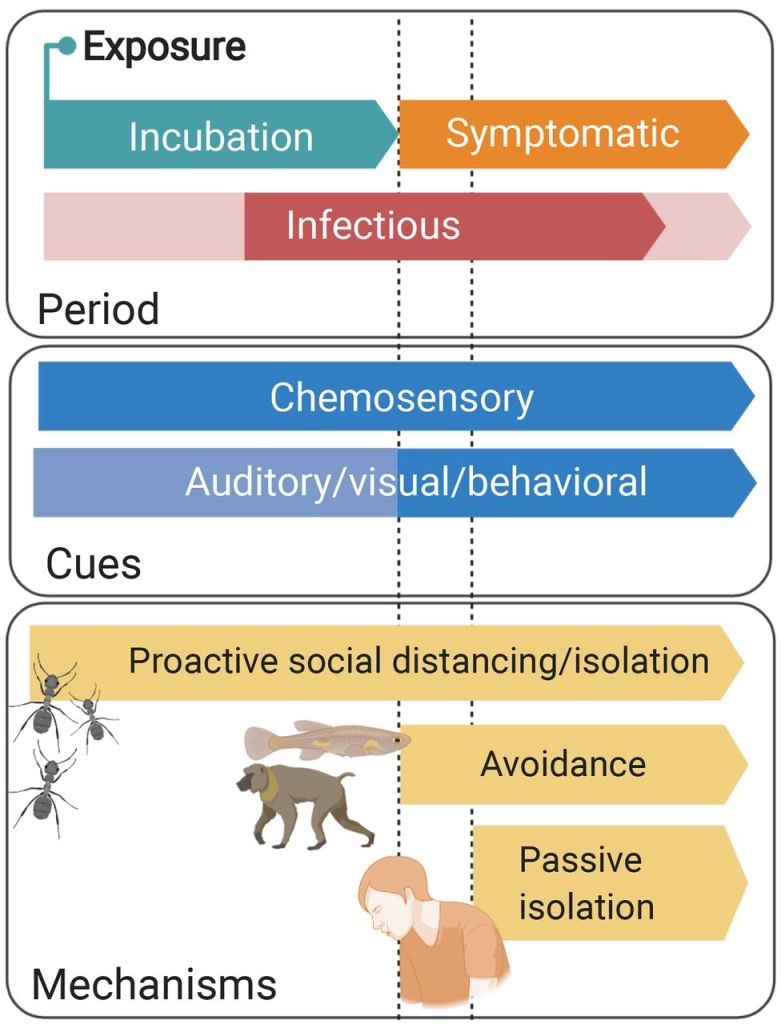

Sickness behaviors are a common host response to inflammatory challenges such as infections. While these behaviors may limit pathogen spread (e.g., through passive self-isolation) or conserve energy for costly immune responses (behavioral resistance), they may come with social costs. For instance, social withdrawal may lead to reduced parental care, social investment, or competitive interactions, all of which are important for the individual’s fitness. Therefore, animals may continue engaging in social interactions despite being sick (behavioral tolerance). Our lab studies several facets of the balance between resistance and tolerance, broadly asking: when is it adaptive to be sick? We explore this question by experimentally inducing sickness behaviors using immunostimulants in a range of social species, including vampire bats, wood roaches, sweat bees, tree swallows, and bumblebees.

How do animals sense sickness?

Pathogens can induce a wide range of changes in host social behavior, including avoidance, enforced exclusion, and proactive social distancing. Many of these responses depend on the ability to recognize infected individuals, raising key questions about the sensory perception of disease cues. We explore this topic using vampire bats and other neotropical bat species to investigate how immune challenges alter olfactory profiles, vocalizations, and visual cues and how conspecifics detect and respond to these cues behaviorally.

Co-evolution of host social behavior and infectious pathogens

Immunostimulants are commonly used to study the social costs and physiological benefits of sickness behaviors. Still, far less research has focused on actual pathogens that have co-evolved with their hosts. Yet, the strength and nature of pathogen-induced behavioral changes are central to host-pathogen coevolution. Socially transmitted pathogens, in particular, may evolve counter-adaptations to overcome host behaviors that limit transmission. Vampire bats host a variety of bacterial and viral pathogens spread through frequent social interactions, including grooming, food sharing, and aggression. We study the behavioral effects of these naturally occurring and co-evolving pathogens using experimental infections and behavioral observations of individuals when alone and embedded in their social networks. So far, we have collected behavioral data from rabies-infected vampire bats, suggesting strain-specific behavioral responses; however, we intend to explore this in other vampire bat/pathogen systems as well.

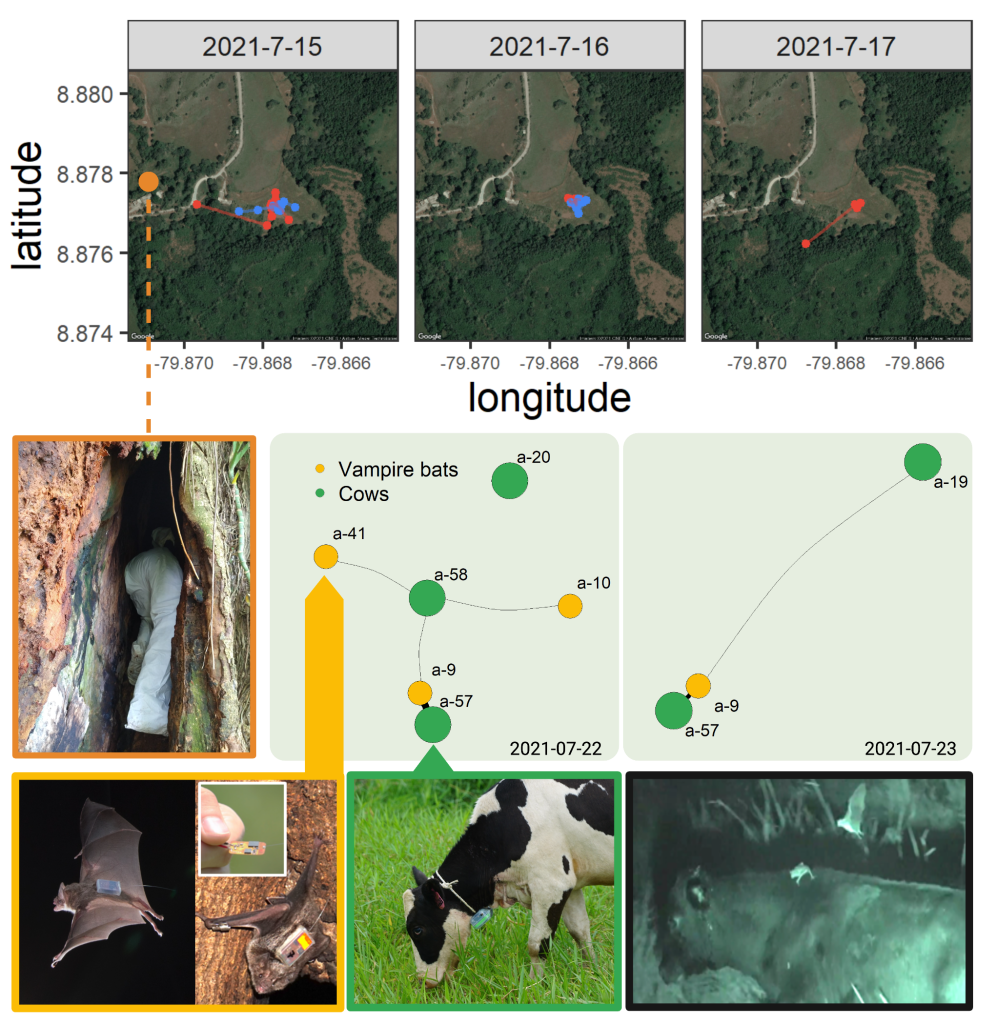

Fine-scale behavioral patterns of cross-species transmission

The ability to predict cross-species transmission is often restricted by a knowledge gap. How does contact between reservoir and host species facilitate pathogen transmission across species borders? Answers to this question are often limited because it is difficult to measure contacts of animals in the wild. We combine (1) biologging approaches such as highly efficient and miniaturized proximity sensors to simultaneously track encounters among many individuals with (2) molecular methods to quantify genetic similarity of pathogens in samples. By combining these methods, we aim to improve inferences about transmission between species. Currently, we work on contact networks of neotropical vampire bats, their host species (livestock such as cattle), and co-roosting bat species. In the future, we aim to extend this method to investigate fine-scale behavioral interactions in other systems that involve contact between animals or their use of shared spatial locations.